A symphony in a case, versatile and portable, the accordion serves the immigrant well. The accordion itself was born of diaspora. In the mid-19th century, early versions of the instrument found their way to the Italian hill city of Castelfidardo, the continued home of accordion manufacturing. While most accordions come from Castelfidardo, a great many Italians in America came from the mezzogiorno — regions in the south of Italy, like Calabria and Sicily, where accordionist Joseph Natoli’s roots lie.

Growing up in Ohio, Natoli’s childhood was filled with music. His grandfather, Joseph, and father, Frank, played the accordion, often accompanied by his uncle’s guitar at family gatherings and picnics. They played all the traditional Italian music. And like many Italians in America, Natoli’s father embraced jazz.

The cadence of the Italian language complements jazz. Italian immigrants, and sons of immigrants, like guitarist Eddie Lang (Salvatore Massaro) and violinist Joe Venuti were prevalent in early jazz. Before the British Invasion of the mid-1960s, accordions and Italian melodies and sensibilities peppered American popular music.

Natoli’s father practiced his accordion in the living room, moving the air between his hands — waltzes and polkas; bebop and swing — shaping the sounds of a thousand crossings. “I used to listen to my dad practice at night and I became enthralled,” says Natoli, “Dad agreed to take me to a lesson.”

His father studied with Mickey Bisilia, a nationally renowned accordion teacher who happened to be based in nearby Youngstown. Bisilia trained champions, and was initially uninterested in such an inexperienced pupil. But after hearing the 7-year-old play a few beginner pieces his father had taught him, and after testing his ear, Bisilia was convinced he could mold the young man into a champion.

“He taught me, and all his students, what the true meaning of excellence is,” says Natoli, “and that has sustained me throughout life for anything I have pursued.”

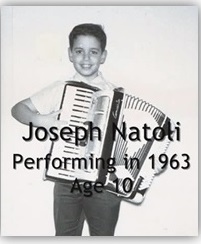

Joseph Natoli, age 10, 1963. Natoli won first place state and national in his age category every year he entered.

Under Bisilia’s tutelage, Natoli would go on to dominate accordion competition. In 1962, after one year of lessons, 8-year-old Natoli won first place in his first state contest. That same year he placed first in the national AAA championship. He won state again the next year, second place nationally. From there he won first place state and national in his age category every year he entered. At 13, Natoli became the youngest person ever to win the all-ages open virtuoso Ohio state championship, and at 18, the second youngest person ever to win the all-ages open virtuoso AAA national championship.

Joseph Natoli, age 13, 1967. Natoli won first place in the State of Ohio Open Virtuoso competition that year, performing the final movement from Aram Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto In D Minor.

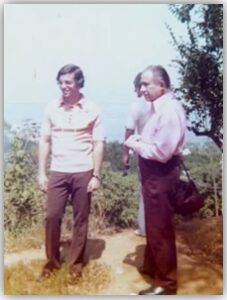

Joseph Natoli, age 19, and Mickey Bisilia, in Caracas, Venezuela at the 1972 Coupe Mondiale.”I expose my good students to the finest classical and best jazz music that I can get my hands on,” Bisilia wrote in Accordion World, “I saturate them with this material to their feeling and liking. From there on, the Road is paved – and the student eventually becomes a fine musician first – and in most cases ends up by becoming a champion as well.” Natoli missed the world title that year by 0.17 of a point, placing first runner-up and was the only one of the top three performers receiving a sustained standing ovation on the final concert.

Joseph Natoli’s music is unrestricted by barriers of genre or era. His voicings are complex and modern. His melodic sense, informed by echoes of the old world. He moves gracefully between classical and jazz, composition and improvisation, acoustic and digital. He has released three completely original CDs that he labels Chameleon Volumes 1, 2 & 3, because they exemplify the diversity of musical thought running throughout his original works.

The family is paramount in Italian culture. Family, the love of his father, first brought Natoli to music and, ultimately, to his first contest stage. And that love brought him back.

In 2008, Roland held the first US V-Accordion competition in Los Angeles. Natoli, by then middle-aged and well accomplished, entered. He didn’t need the title. He wanted the first place prize — a digital Roland FR7. Natoli’s father had grown ill and too frail to play his heavy acoustic accordion. Natoli figured the lighter FR7 might be just the thing to unmute his ailing father’s hands. He won, and presented the FR7 to his father, playing for his original inspiration at his bedside, unknowingly, for the last time. The senior Natoli died shortly after receiving his son’s final gift.

Building on his boyhood championships, Natoli would become a prolific and accomplished performer, composer, publisher and teacher. Having mastered the acoustic, he would explore endless orchestral ideas with the digital accordion. If a door should close on his way (or his thumb — as happened on the way to his first recital), he would channel that into opening another.

Coming soon: Part 2 of the HMC profile of Joseph Natoli will explore his original compositions and his work championing the accordion through his organizations JANPress Music publishing, JANPress University, and GR8 IDEAS symposium.